Walter Lippmann (1889-1974) was an influential journalist who founded the New Republic and was heavily involved with the American government during World War I. He wrote of journalism as a system for “manufacturing consent,” a phrase famously picked up by Noam Chomsky in his book Manufacturing Consent.

Sidney Blumenthal writes in an afterword to a recently reissued volume of Lippmann’s that:

Lippmann had ferried from the offices of The New Republic, located in New York, to the White House, where he helped work on speeches for Woodrow Wilson. After the entry of the United States in the world war in 1917, Lippmann enthusiastically accepted an appointment as the U.S. representative on the Inter-Allied Propaganda Board, with the rank of captain. But Captain Lippmann soon crossed swords with George Creel, chief of the Committee on Public Information, an official federal government agency that whipped up war support through jingoism. When Lippmann submitted a blistering report in 1918 on how the committee manipulated news to foster national hysteria, Creel sought his dismissal — and Lippmann quit his post to assist the U.S. delegation at the Versailles peace conference. The year following the war, 1919, began with Wilson greeted as a messiah and ended with him politically broken and physically paralyzed. His collapse personified the wreckage of Progressive idealism. Lippmann focused his attention on the part played by the press.

I have a little file on Lippmann (which fact he might find amusing) accumulated through some related research into American preparations for the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Lippmann was involved a semi-secret (passwords, guards on the doors of the building) organization put together by President Wilson known as the Inquiry.

The Inquiry was an attempt to apply rational modes of planning to resolve boundary problems, questions of ethnic identity, territoriality, as well as economic restitution following the war.

Lippmann was a major player in the Inquiry, part of the original Executive Committee on a salary of$500 a month, a considerable sum (about $6,700 in today’s money according to the consumer price index calculator here).

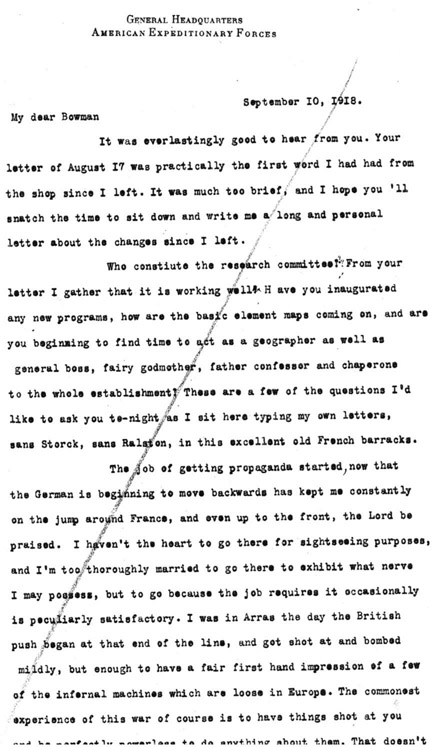

After this Lippmann moved to Europe to “get propaganda started” as he said in a letter to Isaiah Bowman, the geographer now in effective charge of the Inquiry. This was September 10, 1918, just 2 months before the Armistice. (see reproduction below; the line through it was made by Bowman who did this as part of his filing system).

In 1919 Lippmann wrote a short piece describing his take on the war for the Yale Review. One of his points was that it was now necessary to “reconstitute governments” specifically the German government. Lippmann knew that public opinion would be against this, but Lippmann was insistent that Germany (and Yugoslavia) form a government.

Therefore the “most urgent task” of the Conference as Wilson “who saw the problem clearly” knew, was to feed, strengthen and help Germany.

This is how Lippmann describes Wilson’s philosophy:

it is a conviction that the world needs not so much to be administered as to be released from control. It is a state of mind which in its deeper phases acts passionately on the doctrine of consent, the ultimate righteousness of popular judgment, a warm hatred of imperialism, and a quick sympathy with rebellion against political despotism. In the more temperate zones of its feeling it leans toward free trade and a philosophical laissez-faire.

That is an excellent description of neoliberalism!

But Lippmann says that Wilson made a mistake by misreading public opinion in Europe. Wilson, says Lippmann, absented himself from the decisive preliminary stages of the peace conference because he (Wilson) operated under the belief that the people would by common consent indicate their desires. He quotes a key Wilson phrase: “statesmen must follow the common clarified thought or be broken.”

Lippmann is blunt about what then happened to Wilson:

in an increditably short time the popular forces in the middle classes, supposed to be behind Mr. Wilson, regrouped themselves behind special interests. The result was that in the summer of 1918 Mr. Wilson commanded the support of practically the whole working and middle classes in every allied country, by Christmas his only fervent supporters were a section of the working class somewhere about the left center.

This was the beginning of the Wilson as naive-failure-in-the-face-of-realpolitik meme, one which by and large still infects the historical narrative about Wilson.

As Bumenthal points out “Public opinion was not a free marketplace of ideas, but was channeled and polluted by the managers of news…”.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Tagged: Walter Lippmann, WWI |

Leave a comment